One of the great things about taking some time away from organised (office) work is the possibility to experiment, think and rediscover one’s core interest. I’ve seen so many great educational activities during my time of active employment at EUROCLIO, and now I had the chance to play around with some of the inspiration I met along the way. Working together with my mother Els Thijsse (Studio Progress), who is an accomplished artist and art educator, we tried out a workshop which combined local history and art.

In 2018, Scheveningen, a fishing community’s village since time immemorial, marked 200 years since the establishment of a badplaats (meaning as much as a bathing/beach place). One of the many activities included the establishment of historical information points at the local library, aiming to facilitate public education, including extra-curricular activities for (young) kids, about the local history of Scheveningen.

One thing led to another and before we knew it, we had a workshop concept developed around the word haring:

1. The haringkade: The dock along a canal dug in the mid-nineteenth century which enable the herring to be shipped further inland.

2. Keith Haring: The famous graffiti artist of the 1980s.

For the first part, I did two things:

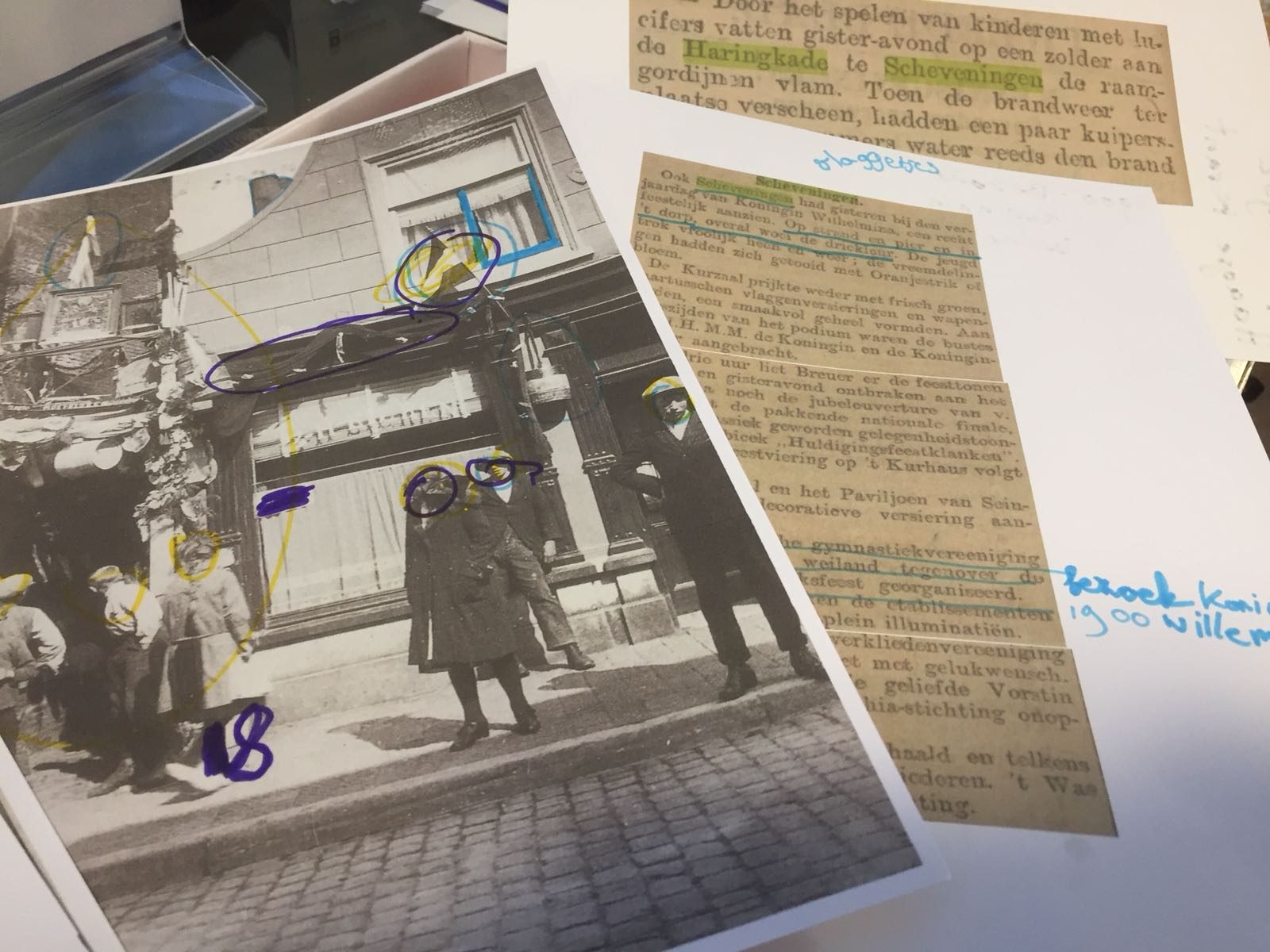

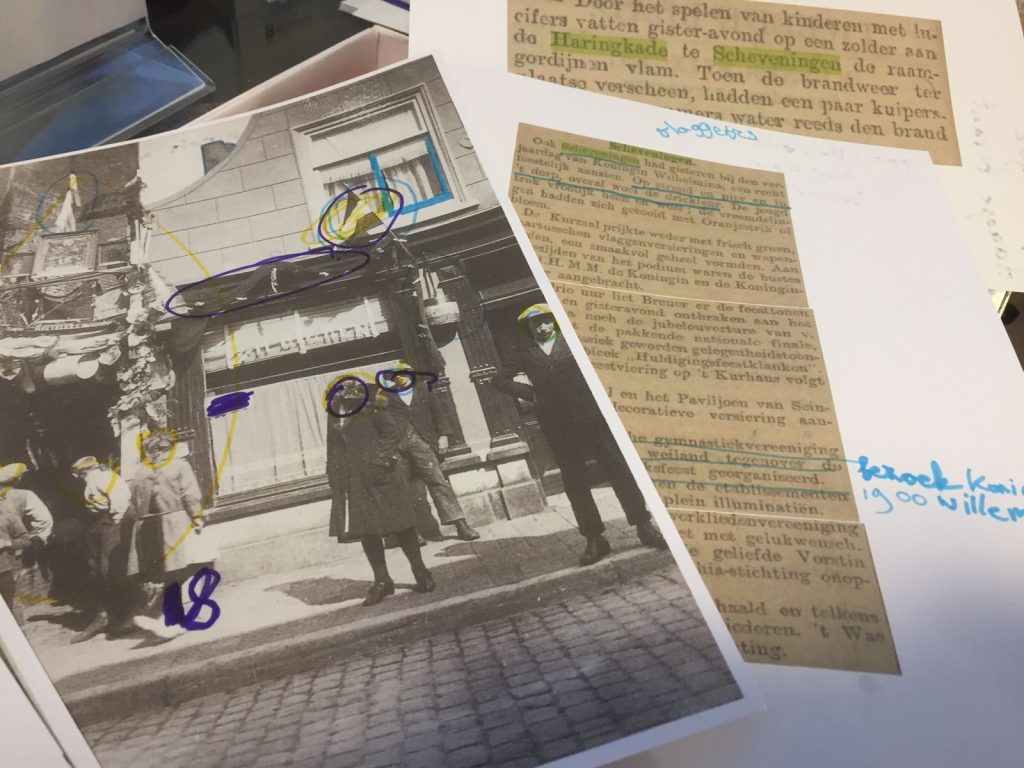

1. Working in a local library, which seeks to help kids learn local history, I made sure I worked with primary sources (mainly newspaper clippings and photography) related to only the Haringkade (with an occasional source expanded to include the other side of the same canal, namely the Havenkade). This approach helped to make history very tangible to the kids who know the local geography very well. In particular as the canal itself was dredged and the last today hosts a skate-park, playground and playfarm.

2. In order to make sure the history was meaningful to the kids, the youngest being 6 years old, the sources I selected dealt only with kids themselves.

With these two criteria (haringkade/havenkade and kids), I selected sources using several local history books, but mainly the magnificent Dutch online newspaper archive platform Delpher. In addition, I chose to focus on the period 1880-1920, because it seems that this was the period of significant change in the character of Scheveningen.

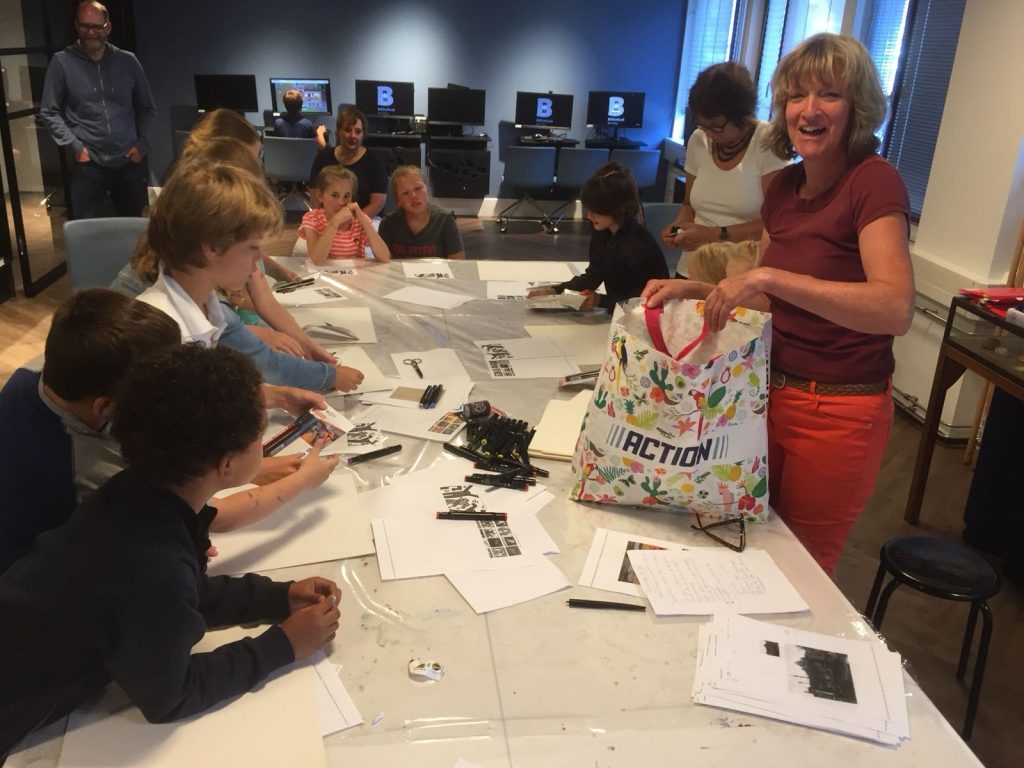

My mother, in the meantime, prepared an approach around Keith Haring, in which she sampled how his artistic style could be seen to have similarities to prehistorical cave paintings. Capturing only the essential form with thick lines. I liked how she considered the very basic ingredient of historical consciousness in her introduction, while the remainder of her time with the kids was to help them paint their own Haring-esque works.

The workshop took place on 20 June with 16 kids (ages 6-12). As an introduction I gave them an iconic Dutch candy, a Haagse Hopje, and asked them if they knew what it was and where it may have come from – in order to reveal that in fact this candy was developed on this one street – the Haringkade, at the chocolate factory Rademaker. Then, I explained to them the basic work of the historian, to find out what happened in the past. When I asked them if they could tell me what they thought had happened in the past, their responses ranged from wars to dinosaurs. I surprised them when I said that many kids have lived in the past. So also everything that they had experienced as kids, counts as history!

The fun started when I asked them to work in four groups, loosely organised on the basis of their age, but even more so on their self-expressed interest in reading, telling stories, or imagining. I gave them four sealed envelopes which had four specific themes: thrilling Scheveningen, fun Scheveningen, every-day Scheveningen, and changing Scheveningen. Their task was to look at the printed sources in the envelopes and identify elements in the sources.

The group dealing with ‘thrilling Scheveningen’ had most textual sources. These sources included articles about kid-related events on the haring- and havenkade: kids falling into the water, kids hitting other kids, kids trying to save a dog from being killed by other kids and so on. I asked the kids in this group to read these articles (which were written in not so easy to understand Dutch), agree on their favourite story and prepare to explain the story in their own words to the other kids.

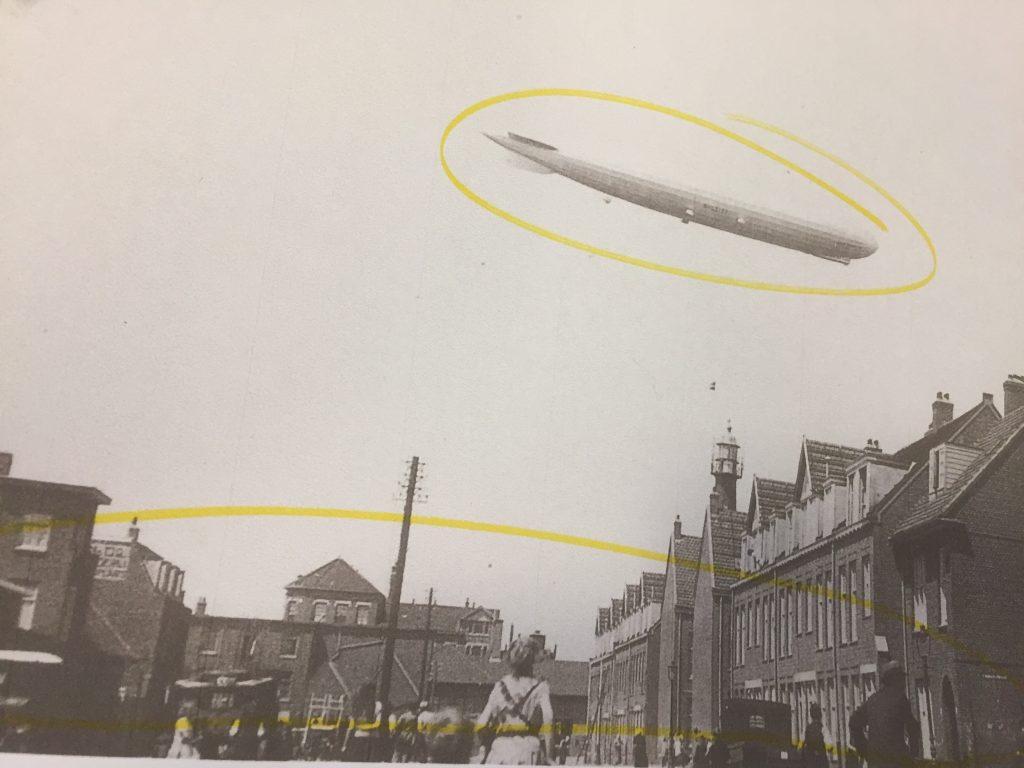

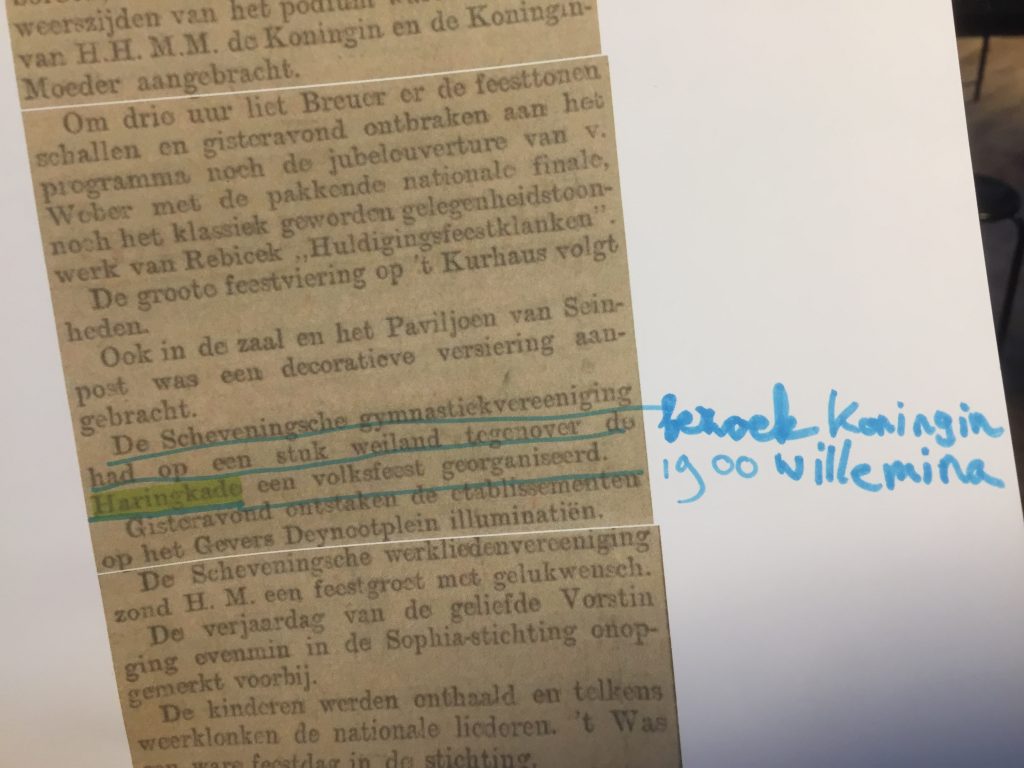

The group dealing with ‘fun Scheveningen’ had a mix of textual and visual sources related to festivities, including celebrations around the arrival of the herring and two historical royal visits to the village, which of course had passed by the haringkade. I asked this group to try to identify what kind of festivities the sources showed, which elements they do, or don’t recognise from festivities they had participated in (like King’s day) and also if they could shortly summarise what had happened and tell it to the other kids.

The group dealing with ‘every-day Scheveningen’ had only visual sources, showing a variety of kids in different situations, including playing, working, posing with family and on the streets. I asked this group, or younger and somewhat less-focused kids, to try and study the faces of the kids on all the pictures, and to see if they could imagine how they felt on the source, and if possible why. I asked them to pick individually the source they liked best, and why, and share this with the others.

The final group, with the youngest kids, got the ‘changing Scheveningen’, including only visual sources of sometimes the same locations but from different decades. I asked them simply to find the differences and try to describe them. In one case of a very young child, I had a source of a road being built, and asked her – in also looking to the source with that street later being full of houses – to paint new houses on the empty street.

The final round was a wrapping up round, in which the kids got to share their stories and conclusions. For every source or story, I knew the exact location. So when a child had said their piece, I put a small sticker on a big canvas holding a map Scheveningen – providing the group with a summative visual of all the rich, and very local, history they had studied together.

This is where we left the cognitive domain and my mother quickly introduced Keith Haring, as said above. The kids easily transitioned from the historical activity, to the artistic activity. All of them were really positive at the end of the 2 hours work – and, so were we!

This experiment has strengthened my belief in the following:

· Doing local history locally with local kids makes a lot of sense, and there is a lot more potential to do this with older students, and maybe also adults.

· Working with primary sources can be done on a very young age. The idea that historians need evidence is not at all too complex for them to understand.

· Public spots, like libraries, are excellent locations for cross-sectional work, like what we did with history and art.

· Scheveningen village has seen a lot of developments. It offers good multiperspective narrations of rich/poor, traditional/industrial, multicultural societies.

Thanks Studio Progress, Historisch Informatie Punt and Feest-aan-Zee of the opportunity to experiment, and of course EUROCLIO – European Association of History Educators for all the inspiration provided!

Some photographs of our work session below:

Leaving you today with a set of questions:

- What is your experience with working with local history?

- Do you know more successful applications of combining history and art education?

- What do you think is missing in the approach above? (be honest :-))